| In

1983 the FCC reassigned UHF channels 70-83 for use by mobile telephony

- the

beginning of the cell phone era. A few decades later, with the DTV

transition about to

begin, UHF channels 52-69 were also reallocated for other

telecommunication purposes. At the same time, a freeze was put on all

new

applications for channel 51 in order to preserve a buffer zone between

television broadcasters and the newer services. All these changes

effectively cut the UHF TV band down

to almost half its former size.

Thus,

in two fell swoops, all the stations

that had been broadcasting on those discontinued UHF channels were forced

to change frequencies. Furthermore, it was determined that

the

VHF Low band, because of its sometimes unpredictable transmission

characteristics, was not well suited for the DTV age, so most of the

channel 2-6 stations also migrated to new frequencies - mainly into the increasingly crowded UHF band. Adding to this chaotic

scramble, many of the

stations that had been operating on a formerly acceptable channel

also had

to change their frequencies in order to avoid interference amongst

all the signals that were now swimming in a smaller pool.

But here's where it really gets confusing:

When

all these changes were in the planning stage, someone realized that the

public might have a hard time figuring out all the new channel numbers. And

after all, with due respect to the longstanding stations, those channel

numbers had represented their very identity for many years. That

channel number was their brand name so to speak, and no

self-respecting

station

would want to part with it. So in order to preserve this aspect of a

television station's identity, the geniuses-that-be devised a method

whereby digital tuners would display the station's old

familiar channel number even though that station might now be operating

on a different channel, perhaps even in a completely different

frequency band.

So, ever since 2009, what you see on your screen is not necessarily what you are getting.

For example, The South's First Television Station,

WTVR in Richmond, which had been operating on VHF channel 6 since 1948, has actually been transmitting on UHF

channel 25 following the digital transition.

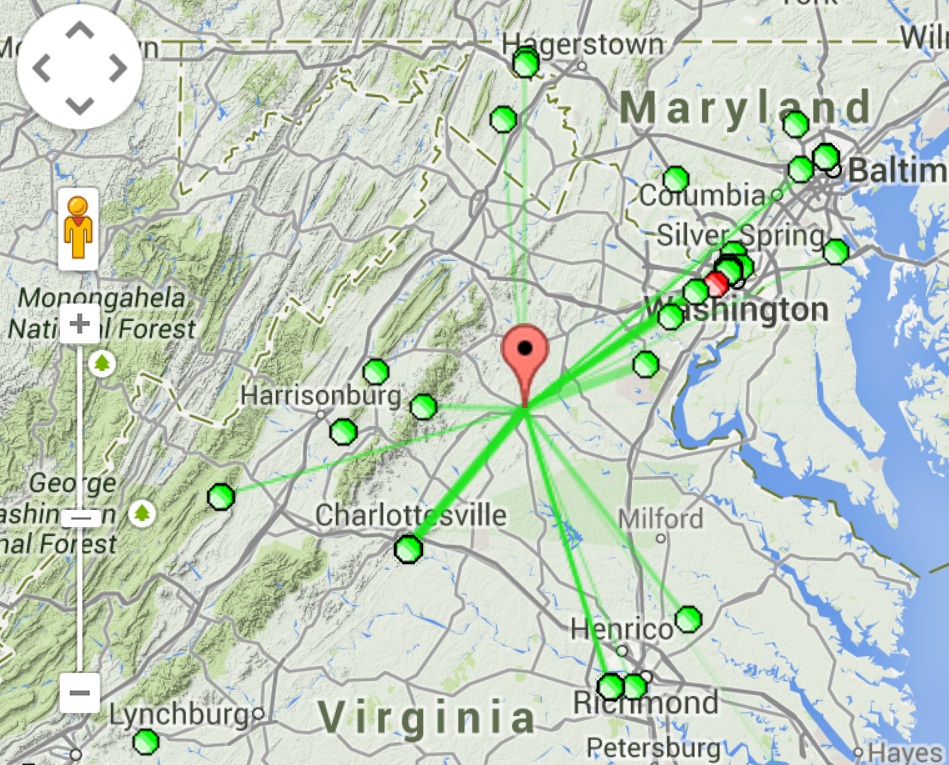

Charlottesville's million

watt

powerhouse, WVIR, NBC 29 to those of us living in central

Virginia, was bumped up to channel 32 in the DTV

shuffle.

Staunton/Harrisonburg's PBS station, WVPT, which had

previously been seen on UHF channel 51, is one of the few stations that

switched

from UHF to VHF when the transition hit. They now operate

several low powered transmitters throughout the area on channel 11.

Not every station had to abandon their formerly analog channel however. Notably,

channels 7 and 9 from DC, channel 12 in Richmond, and 13 in Lynchburg

are still using their original VHF frequencies.

Meanwhile,

there is also a channel 13 and an 11 in Baltimore, so even your digital

tuner might get confused if you're in a location that can receive

multiple stations on the same channel. |

It's all relative. |

The

funny thing is that when you tune your digital TV set (or DTA

converter box) to one of these stations it will show up as channel 6,

channel 29, or channel 51 just like it always did. This happens because

there is data embedded within each station's signal that

tells the tuner what numbers to display on the screen regardless of

what channel the signal is really coming in on. The displayed channel

number is usually referred to as the "Virtual Channel" or simply the

"Display Channel" as opposed to the "Radio Frequency" or RF / Real / Physical Channel / etc.

So why am I going on and on

about this? For one thing it explains why, when you are first setting up your

new digital TV tuner, you can't just punch in a number and expect to

find your usual stations where you think they should be. A digital TV or converter box has to go through a scanning

process to find out which channels the available stations are really on before it will let you

watch them. But here's one of my top secret tips that may help you find a particular station more easily:

I've discovered that some digital TV tuners will go straight to

the station you want if you punch in its Real Channel number on the remote control.

|